It's Not Easy Seeing Green - Twelve Artists Share Their Favorites

|

Next

It's Not Easy Seeing Green:

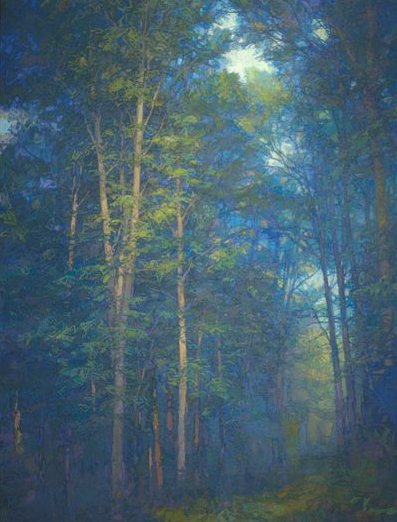

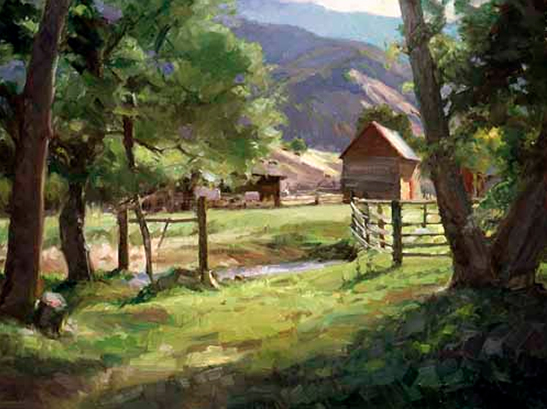

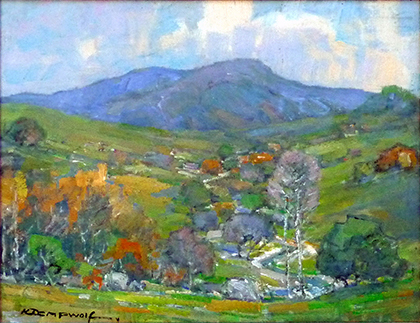

Twelve Artists Share Their Favorites The Color Green I just use viridian green, as well as mixtures with ultramarine blue, cobalt blue, and ivory black with cadmium yellow and lemon yellow for my greens. I don't have any special mixtures, but just fool around until I get the colors I see. My main tip on painting green is to find the purest green in your subject to start with and then compare everything to that. If you look at each green by itself, you will make them all the same in intensity. I have noticed a discrepancy in perception of greens with (my wife) Ellen on some paintings. . . However, I have kind of seen this problem for a long time and have consciously tried to shift the play of my greens to include a wider warmer range, or at least to mix it up a bit between paintings. Beyond this, I should note that in the same way Caravaggio is reputed to have said that blue is the poison of colors, I have an aversion, perhaps strange for an eastern landscape painter, to greens and blues. So it is no wonder why I kick the color around so much in most of my landscapes. Green is an important and challenging color. It can vary from deep blue black to pale almost yellow or pink. You have to think of it as being made from many of the surrounding colors, and as an important element in the overall color scheme. Usually I am making my greens by first pulling the blues from the left side of my palette into the yellows on the right. The reds, both alizarin and cadmium are pulled into the top, and white is kept to the side as needed. I keep viridian on the palate as a boost, and have found that at this time (Spring) I keep a permanent green light for that crazy electric green that is the color of emerging leaves. OK, this is just a start on the mystery of mixing color... My greens are made with ultramarine, cobalt blue, cadmium yellow deep, yellow ochre, and then a variety of reds. In the greens on this painting, there are a lot of cool dark greens made with alizarin crimson, viridian, ultramarine blue and the two yellows. I don't use cerulean, but Marc Dalessio gets great greens, so it must work. My palette varies slightly depending on where I am, but typically it is at the top: titanium white, cadmium yellow lemon, cadmium yellow deep, yellow ochre, transparent orange, cadmium red light, alizarin permanent, burnt sienna, and asphaltum. On the left side from bottom to top: ultramarine blue, cobalt blue, viridian, and permanent green. I keep these on my plein air palette and usually keep my studio palette to these as well. Sometimes I add a few to my studio palette: cadmium green, cadmium orange and occasionally sap green. These are all Gamblin colors. A few of them are particular to Gamblin such as transparent orange and asphaltum. Gamblin makes some great transparent colors. I found cadmium orange to be too cool and harsh for me so I use their transparent orange instead because it warms up a green mixture nicely. I also use it with blues to make the green color we see toward the horizon in the sky without it really going green. Asphaltum is a nice earthy transparent brown color. I usually start finding the values in my paintings with a mixture of asphaltum and ultramarine blue. Another Gamblin color I sometimes use is transparent earth red which is a nice alternative to burnt sienna.

When I am oil painting I only buy two greens, chrome oxide green and pthalo green. I don't usually use them straight out of the tube but will when the color is appropriate, which is not very often with the pthalo. I usually buy professional grade oils from Daniel Smith or Utrecht. What is probably most important to me is to change the temperature of the green as you change its value and try to find reds and browns to contrast whenever possible. I will often start a "green" painting on a venetian red under-painting. My mixing of two colors to make green includes ultramarine blue, pthalo blue, cadmium yellow medium, hansa yellow light, and yellow ochre. In the end every color on my palette is used to tint, warm, cool or neutralize my greens.

I typically do not have a green on my palette. I took green off early in my career. Tennessee is nothing but green in the spring and summer. If your paintings don’t have a variety of greens they will fail. Early on when I did use green, I noticed all my greens looked the same. I had the bad habit of dipping into the same green for all my greens. My solution was to get rid of the green on my palette and mix for the object I was looking at, hence giving me the variety I needed to create interest in my painting.

I have viridian green on my palette. I like it better than other tubed greens because I feel it is more versatile than other greens. It can be a very cold green when mixed into white. It can look almost blue and I use it in skies very often. When you add yellow to it, it becomes a very warm spring green like sunlight on grass. You can bend it warmer or cooler by adding the analogous colors (colors to either side of green on the color wheel) blue-green to cool it or yellow-green to warm it up. If you add some complementary color to it like red, red-orange or red-violet you can reduce the chroma and gray it down according to how much you want to reduce the intensity. Another way to cut down on the chroma of pure viridian is to mix it with yellow ochre, or, for a darker tone, raw or burnt sienna. Earth colors are great for greying almost any color.

Over the years I have slowly changed my greens to adapt to my increasing sensitivity to the colors in the landscape. I use these same greens in my studio work. When I began teaching myself how to paint in 1968, I learned how to mix greens from blue and yellow. Some years ago I began investigating how the Old Masters mixed greens from yellow and black, and added that to my repertoire. Yellow ochre and black, especially, makes wonderful smoky dark greens and grays. Generally though, I prefer to mix greens from cobalt or ultramarine blue with either cadmium yellow light or lemon, or cadmium yellow medium. I can make a very cool mix from lemon yellow and cobalt and even add white for more coolness, or warm the greens with ultramarine blue and cadmium yellow medium, which makes a nice muted warm green. I use cadmium red light to further gray and warm my greens, or alizarin crimson for a cooler green-gray. Cadmium orange is great for modulating into those warm cedar tree tones we get in the Winter. I generally start a painting by identifying the dominant green masses in the foreground, and then mix a color string in my palette from warm to cool of that mass color. In this way, I can simply pick up the correct temperature and modulate the value to match. Warm greens approach from the foreground and cooler, lighter-valued greens recede in the background. The majority of my painting will be composed of colorful grays, with just touches of higher chroma colors at the finish to bring it all together. Tube greens I use sometimes: sap green, viridian.

About green. I thought I understood all the colors--but Missouri had to teach me a thing or two about green before I could even start to begin. With pastels I never blend but only layer so a wide range of colors is pretty important. Oils, acrylics and watercolors are different though. My basic palette for green consists of warm and cool blues mixed with warm and cool yellows. Pthalo green is the extra spice for power but I always desaturate it with other colors around my palette - even using reds sometimes. Sap green is nice and for the desert, chrome-oxide is pretty essential. If I want a real charge, I mix the greens with a touch of any of the cobalts - especially in watercolor. Have to admit a Daniel Smith's occasional treat (like Green Gold) can be a real treat once in a while.

Green is one of the colors I really love, and since we only see it for just a few weeks in the Spring here in southern California and then not again for the rest of the year I will use it, usually NOT right out of the tube. I love the Utrecht Brilliant Green. It has more body than the Windsor Newton green and so when I want a punchy green I start with the Utrecht. I will mix a yellow light in it to punch it up even more, or a yellow deep to bring down the intensity of the green. In the attached image there are a variety of greens, the brightest being under or near the California Live Oak on the right and then repeated in the tree towards the far left. The green gets toned down a bit as we head towards the horizon, there are already areas that are changing towards the familiar light brown found all over the southern part of the state. Even in the middle of Summer I will include a little green under or near the large oaks, since they gather the light morning mist and drop it keeping some of the green in the shadiest areas.

I don't use a green. I mix my own. There is a short video on youtube See: Secrets of the Old Masters - Mixing Beautiful Greens from Black, All artwork copyright the artists.

|

Become an Artist's Road Member Today!

Already a Member?Log in here. To renew your membership, log in and follow the links. Search the SitePerspectivesNot ready to become a Member yet? Subscribe to our free email postcards, "Perspectives". Enter your email address here.

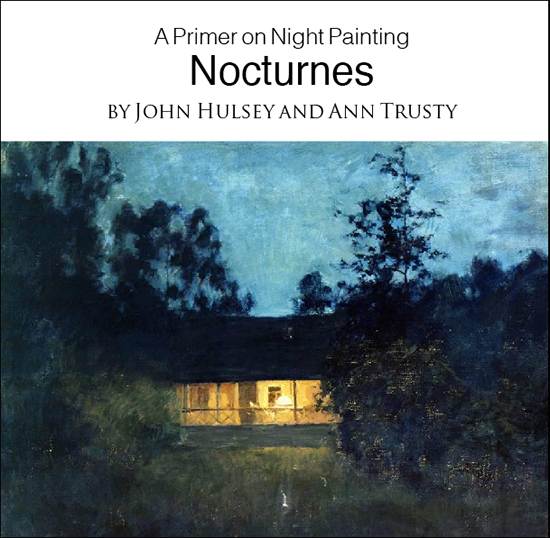

Member ContentFree ContentThe Artist's Road StoreNocturnes - A Primer on Night Painting Filled with inspirational examples by the masters of nightime painting, this little book is sure to fire up your creative energies. Never tried painting at night? We show you how it's done with a step-by-step-oil demo and a tale of night painting in the wilds of Rocky Mountain National Park. The Primer on Night Painting - Nocturnes is a 7 x 7" PDF download with 40 pages of text and images. It includes a gallery of paintings by masters of the nocturne, information to inspire and encourage you in your plein air nocturne painting, an illustrated step-by-step demo and tips for working in pastel and oil. Also available in a softcover edition. Check out the tools and other products that we use in our own art and travels in The Artist's Road Store. We only offer things for sale that we enthusiastically believe in.

About Us

|

Voices of Experience:Richard K. Blades

Voices of Experience:Richard K. Blades

ing Watercolors

ing Watercolors

Nocturne Notes

Nocturne Notes Inspiration in Monet's Gardens

Inspiration in Monet's Gardens

The Watercolor Medium

The Watercolor Medium

The Perspectives Archive

The Perspectives Archive