From Plein Air to the Studio - Two Case Studies

If you are not a member and would like to receive all of the benefits of membership -- including access to this Members Only section -- click here and complete the online application and payment process. You will be given immediate access to premium content on the site. The complete Perspectives Archive Step-by-Step Demonstrations of Painting in Watercolor, Pastel and Oil Step-by-Step Painting Videos Voices of Experience - Insightful, informative full-length interviews with prominent professional artists Professional Tips to help you in your creative development and travel adventures Members' Gallery - Show off your art and include a link to your website, blog and/or Facebook page Going Mobile - Our essential gear/materials checklists for the traveling artist Artist Abroad - Top phrases in French, Italian, Spanish specifically for artists Valuable new members-only content added regularly! Members only discounts on many of the products in The Artist's Road Store You will automatically receive Perspectives - Our free email postcard Your membership is 100% guaranteed if you are not completely satisfied. Click here to join.

|

Become an Artist's Road Member Today!

Already a Member?Log in here. To renew your membership, log in and follow the links. Search the SitePerspectivesNot ready to become a Member yet? Subscribe to our free email postcards, "Perspectives". Enter your email address here.

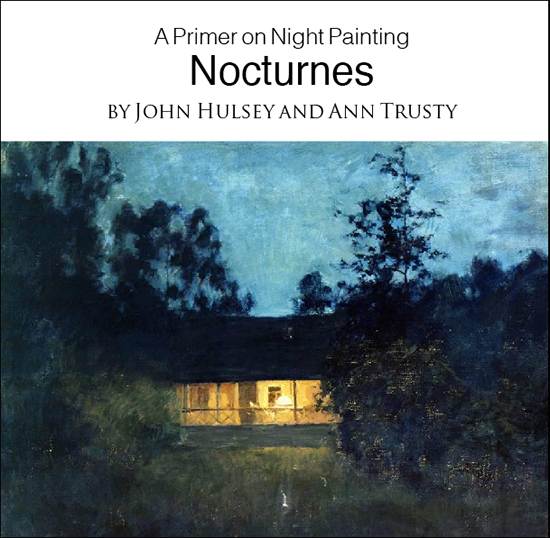

Member ContentFree ContentThe Artist's Road StoreNocturnes - A Primer on Night Painting Filled with inspirational examples by the masters of nightime painting, this little book is sure to fire up your creative energies. Never tried painting at night? We show you how it's done with a step-by-step-oil demo and a tale of night painting in the wilds of Rocky Mountain National Park. The Primer on Night Painting - Nocturnes is a 7 x 7" PDF download with 40 pages of text and images. It includes a gallery of paintings by masters of the nocturne, information to inspire and encourage you in your plein air nocturne painting, an illustrated step-by-step demo and tips for working in pastel and oil. Also available in a softcover edition. Check out the tools and other products that we use in our own art and travels in The Artist's Road Store. We only offer things for sale that we enthusiastically believe in.

About Us

|

Voices of Experience:Richard K. Blades

Voices of Experience:Richard K. Blades

ing Watercolors

ing Watercolors

Nocturne Notes

Nocturne Notes Inspiration in Monet's Gardens

Inspiration in Monet's Gardens

The Watercolor Medium

The Watercolor Medium

The Perspectives Archive

The Perspectives Archive